Mixed methods research has exploded in popularity within social research in the past 20-25 years. It’s easy to see the appeal. Quantitative research can give us a broad picture based on a large sample, with numeric data that can be manipulated statistically, and can help us say what has happened. Qualitative research lets us go deep and explore stories, nuances, and experiences from fewer participants, helping us say how or why things have happened. Combining both (where this makes sense given our research questions) offers us the best of both worlds.

Mixed methods research can be done well or poorly. One key challenge is ensuring that the integration of the qualitative and quantitative components makes sense. Mixed methods studies should not simply be two effectively distinct studies (one qualitative and one quantitative) on the same topic. To be able to combine qualitative and quantitative elements coherently, requires paying attention to our research paradigm(s). There are many different paradigms identified in the literature; commonly used paradigms within social research include post-positivist, interpretivist/constructivist, transformative/critical, indigenous, and pragmatist paradigms (for more background on paradigms, see Mackenzie & Knipe, 2006).

The importance of paradigms in mixed methods

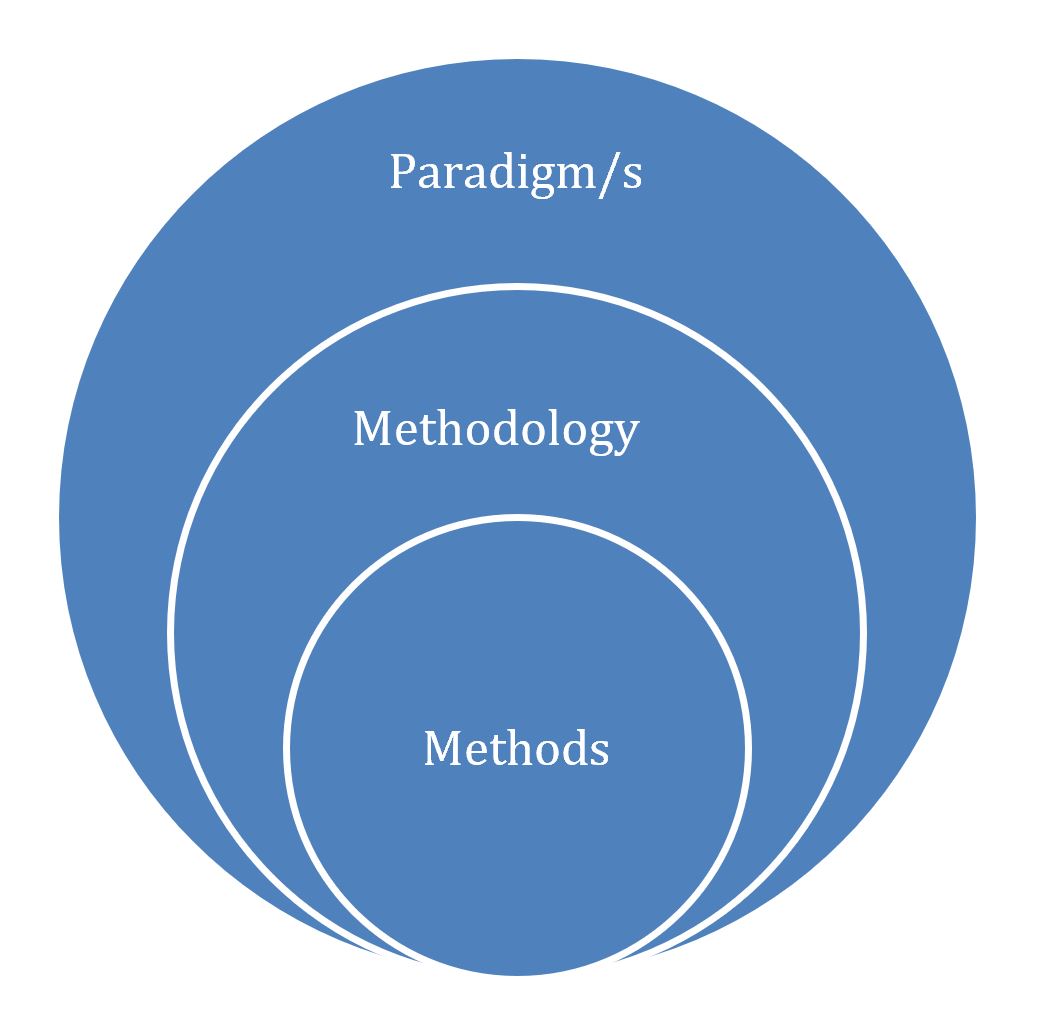

Different people define paradigms differently. This post is informed by

Tashakkori et al.’s (2020) definition that paradigms, methodologies, and methods are three distinct but related concepts, progressing from the most abstract (paradigms) to the most concrete (methods). Our specific methods (ways of gathering and analysing data, e.g. random sampling, questionnaires, thematic analysis) sit within our methodology (big picture ways of doing research, e.g. experimental designs; mixed-methods; survey research), and those methods and methodologies sit within our paradigm(s) (big picture ways of seeing the world).

Mixed methods can be understood as a methodology. Alternatively, mixed methods can be seen as one of three overall “approaches” to research (alongside qualitative or quantitative approaches), within which we might identify a more specific methodology for a particular study such as case study, phenomenology, or grounded theory (any of these can be done using mixed methods). Either way, our research (including both methodology and methods) still sits within a paradigmatic framework – whether we realise it or not.

Many mixed methods research publications are silent on the paradigm/s that framed the research. If we aren’t careful in thinking about the research paradigm/s we are working within, we can end up inadvertently taking steps or making statements that don’t make sense. What we do or say in one part of our study may contradict what we have done or said elsewhere, potentially threatening the coherence, validity, and credibility of our work. According to Mertens (2019, p. 8), “working without an awareness of our underlying philosophical assumptions does not mean that we do not have such assumptions, only that we are conducting research that rests on unexamined and unrecognized assumptions.” This is particularly problematic in mixed methods research where the increased complexity introduced by mixing methods increases the chance of us combining things in ways that are inconsistent or contradictory.

Moving beyond traditional assumptions

To make any sense of paradigms for mixed methods research, we need to move beyond uncritical acceptance of two traditional but contested ideas.

The first is the incommensurability argument – the claim that different paradigms involve irreconcilable worldviews and are therefore incompatible. The second is the binary assumption that some paradigms “belong” with qualitative approaches and other paradigms with quantitative approaches (for more on these two ideas, see

McChesney & Aldridge, 2019). Together, these two ideas pose problems for mixed methods research because of the incommensurability argument: if paradigms for quantitative and qualitative methods are different but cannot be combined, then mixed methods research becomes (philosophically) impossible, meaningless, or (at best) logically inconsistent.

Both of the above ideas are widespread; for example, there are research methods texts (e.g.

here and

here) that still advise students that certain methods belong (either strictly or, more gently, that certain methods “tend to belong”) with certain paradigms. However, we in fact have a large body of literature (especially more recent literature)

disrupting these two assumptions and positioning them as being unnecessarily

restrictive and

simplistic. According to

Creswell and Plano Clark (2017, p. 13),

Mixed methods research encourages the use of multiple worldviews, or paradigms (i.e. beliefs and values), rather than the typical association of certain paradigms with quantitative research and others with qualitative research. It also encourages us to think about paradigms that might encompass all of qualitative and quantitative research.

Strategies for research(ers)

There are three common approaches to situating mixed methods research within a paradigmatic framework. Each of these approaches brings its own challenges that warrant careful consideration.

- A dual/dialectical approach – Some researchers combine two paradigms within a mixed methods study. This could occur through one paradigm framing the quantitative components of the study, and the other the qualitative components, with the findings of these two elements then being presented in dialogue. Alternatively, members of the research team could approach the data from different paradigmatic perspectives and then their differing interpretations could be placed in dialogue. The dual/dialectical approach to mixed methods research seeks to ensure that there is rich dialogue and interaction between the findings and perspectives that come from each paradigm. A key challenge here is ensuring that this dialogue does actually emerge; often, what results is effectively two separate studies (one qualitative and one quantitative) under the same overarching research question/s. Alternatively, one paradigm may dominate the other. Neither of these scenarios really constitutes mixed methods.

- A pragmatist approach – A popular variant of the dual/dialectical stance is the pragmatic argument that paradigms are logically independent (so do not affect each other) and thus can be mixed and matched harmlessly based on what suits the research question/s. This assumption that paradigms can be positioned side-by-side (e.g. within the same research study) without coming into conflict has been described as “the pacifier in the paradigm war”. But can paradigms really be combined so easily? According to Denzin (2012),

“It is one thing to endorse pluralism [or dialecticalism] … but it is quite another to build a social science on a what-works pragmatism. It is a mistake to forget about paradigm, epistemological, and methodological differences between and within QUAN/QUAL frameworks. These are differences that matter.”

A key challenge for those wishing to use a pragmatist approach, then, is to present a clear argument for why this is meaningful and appropriate in the specific context of their research and in relation to the specific paradigms they are attempting to juxtapose.

- A holistic / single-paradigm approach – This is the approach I used for my own doctoral study. Moving beyond the binary assumption that different methods ‘belong’ with different paradigms, many scholars have suggested that “if it suits their purposes, any of the theoretical perspectives could make use of any of the methodologies” (Crotty, 1998, p. 12). Thus, it is possible to select a single paradigm that reflects our view of the world and use it to underpin all aspects of a mixed-methods study. Here, the key challenge is to ensure that this paradigm is actually “lived out” consistently in how the research proceeds.

A brief example of the holistic / single-paradigm approach

The single-paradigm approach is often used in social research, but almost exclusively within a

post-positivist paradigm. In contrast, for

my doctoral research, on teachers’ experiences of professional development, I chose to use an overarching

interpretivist paradigm. According to

Schwandt (1998, p. 221), the goal of interpretivist research is “understanding the complex world of lived experience from the point of view of those who live it”. In my case, the interpretivist paradigm meant that I focused on understanding teachers’ experiences and perceptions in a specific local context, recognising that both qualitative and quantitative data were subjective constructions of reality.

In particular, working within the interpretivist paradigm meant that I:

- Framed my research objectives using language and concepts that aligned with a focus on my participants’ experiences and perceptions

- Collected data only from teachers (and not others such as principals, professional development providers), because it was the teachers whose lived experiences I was interested in

- Accepted the teachers’ accounts (in both qualitative and quantitative forms) as representing their experiences of the world (and did not seek to verify or evaluate their views or triangulate with data from other stakeholders or sources)

- Invited all eligible teachers to participate before using targeted sampling to improve the breadth and balance within the sample

- Collected both qualitative and quantitative data together, so that each could inform the other (for example, teachers completed a quantitative survey during their interview with me, and I captured their qualitative oral comments as they responded to and discussed the survey)

- Did not begin with pre-determined hypotheses, but maintained a stance of openness, including through the use of constructivist grounded theory methods (Charmaz, 2008) and adding a research question to reflect unexpected but important findings

- Held quantitative results loosely and interpreted them through the lens of both the qualitative data and previous research into cultural differences and intercultural communication

- Used both qualitative and quantitative data to form conclusions about most research objectives, and also offered integrated findings across several objectives, all of which treated data as constructions of meaning

- Used quality considerations appropriate for interpretivist research, rather than the typical mixed methods quality criteria which reflect a post-positivist worldview

Concluding thoughts

Social research is hugely important for influencing policies and practices that shape our lives. It is important, therefore, that social research be robust and that both the creators and users of this research have a clear understanding of what the research can and cannot tell us. Acknowledging the paradigmatic positioning of a research project contributes to this, as paradigms inform how the research findings can meaningfully be interpreted (for example, the extent to which the findings can be assumed to apply to other people or groups outside the study’s participants).

There is more than one coherent way to locate mixed methods research within broader paradigm(s). Overall, I suggest that what matters most is:

- That the paradigmatic or philosophical underpinnings of any research study are explicitly stated;

- That both the paradigm(s) and methods selected are suitable to allow the aims and objectives of the study to be met; and

- That researchers demonstrate how the research methods and the overall conduct of the study reflect or acknowledge the chosen paradigm(s), making explicit and justifying their design decisions

In some applied or public sector research contexts, the considerations discussed in this blog post may not seem so important to the funders or end-users of social research. However, the reason we as researchers are often contracted to conduct social research is because of our sophisticated knowledge of research approaches, theories, and processes. Whether funders demand it or not, we can and should weave consideration of paradigmatic foundations into any research we conduct, and ensure that this positioning informs our (explicit) statements about how the findings of our research can appropriately be used. This latter point should be of much interest to the end-users or commissioners of our research and can help ensure that they take our findings forward (e.g. to inform policy or practice) in ways that are justifiable.

What do you think? How have you tried to make sense of paradigms for mixed methods research? How have you addressed these issues in the context of applied or commissioned research? How have you communicated what the paradigmatic foundations of your research mean for how the findings can appropriately be used?

Author Bios: Dr Katrina McChesney is a senior lecturer in education at the University of Waikato, New Zealand. She researches people’s experiences of educational spaces, processes, and experiences, including through the use of interpretivist and mixed methods approaches. Her PhD, completed in 2017, investigated teachers’ experiences of professional development within a major education reform in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

Acknowledgements: The author’s doctoral research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Programme Scholarship and a Curtin University PhD Completion Scholarship.

Interested in learning more about Mixed Methods research? The SRA now offer an Introduction to Mixed Methods course.